Lessons Learned From 'The One-Straw Revolution'

38.4113° N, -122.3954° W

2025.01.16

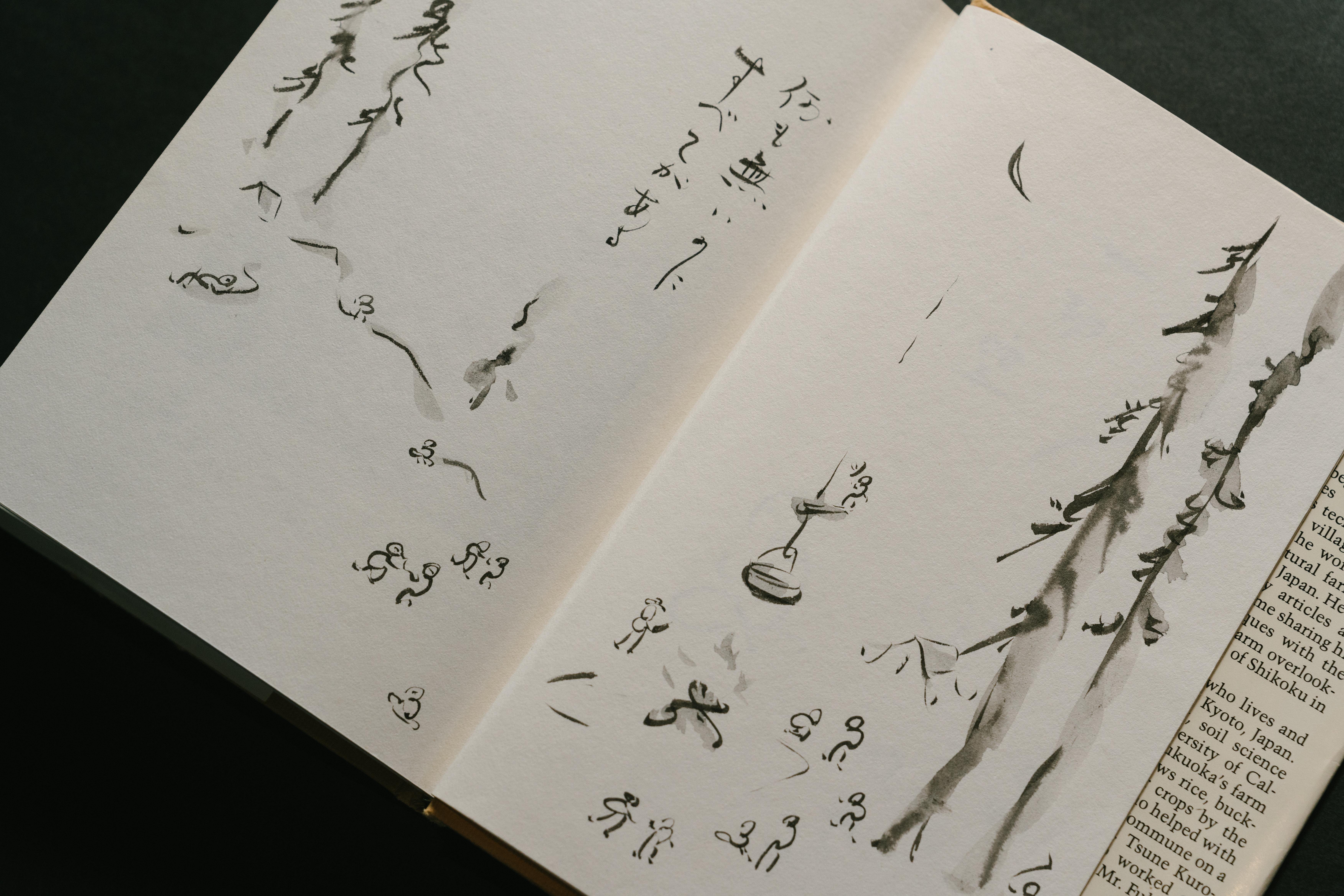

One of the key pieces of literature that influenced our way of farming was Masanobu Fukuoka’s, One Straw Revolution.

The teachings of Masanobu Fukuoka, emphasize a deep respect for nature, the interconnectedness of all living things, and a return to more harmonious, less intrusive interactions with the land. Fukuoka’s ideas encourage farmers to work with nature rather than against it, suggesting that true agricultural success comes from observing, understanding, and mimicking the natural systems that have thrived for millennia.

“If you do not use the plow, you will not need to use the hoe. If you do not use the hoe, you will not need to use the sickle. The ultimate goal of farming is to eliminate the need for human labor altogether.”

Masanobu Fukuoka

The One-Straw Revolution (1975)

Principles of Reverential Farming

At the heart of this way of farming lies the rejection of conventional agricultural methods that depend heavily on tilling, chemical inputs, and monoculture crops. Fukuoka’s philosophy, which he sometimes refers to as "do-nothing farming," advocates for a much more hands-off approach intended to minimize human intervention and allow nature to govern itself. This is not to say that no effort on the part of the farmer is required; rather, the farmer is encouraged to work with nature rather than forcing natural processes to conform to human preconceptions and expectations.

To look at each practice and ask yourself, is this absolutely necessary? What would happen if I didn’t do this? Could I do one less thing (instead of one more) and get a better result? These questions only come about from a deep curiosity and an even deeper commitment to observe copiously before you act.

“The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation and perfection of human beings.”

Masanobu Fukuoka

1975

Fukuoka’s calls his philosophy "natural farming." This principle encourages the use of organic methods—no chemical pesticides, synthetic fertilizers, or herbicides. Instead, farmers rely on composting, crop rotation, and integrated pest management to foster a balanced ecosystem. The soil is seen not as a commodity, but as a living entity to be nourished and protected. In Fukuoka’s view, soil health is directly connected to plant health, and by nurturing the soil, we can naturally promote robust, healthy crops.

Natural farming also places a strong emphasis on biodiversity. Rather than growing a single crop over a vast area, farmers are encouraged to cultivate a diverse range of plants that work together symbiotically. In this system, the plants, animals, insects, and microorganisms all contribute to the health of the environment, with each organism playing its part in maintaining a stable ecosystem. By embracing diversity, natural farming not only reduces the risk of pest infestations and crop diseases but also creates a richer, more resilient farm.

Reverence for Nature: The Heart of Fukuoka’s Philosophy

For Fukuoka, farming was not merely a way to grow food—it was a spiritual practice. Natural farming calls for a deep respect for the land, seeing it as a living entity with its own rhythms and processes. Observing this idea means approaching the land with humility, understanding that nature is an intricate web of relationships that cannot be easily controlled or manipulated.

Fukuoka closes his case with the profound realization that nature, when left to its own devices, often knows best. He reflects on the foolishness of attempting to perfect nature through human intervention, whether it be through excessive irrigation, chemical inputs, or the overuse of mechanical equipment. His message is clear: when we work in harmony with the land, we not only nourish the soil and the crops but also honor the delicate balance that nature has perfected over millions of years.